Behind the headlines and diplomatic spin suggesting that the Security Council is now siding with Morocco lies a more complex reality - one that hinges on the very right that Rabat has spent decades trying to bury: self-determination.

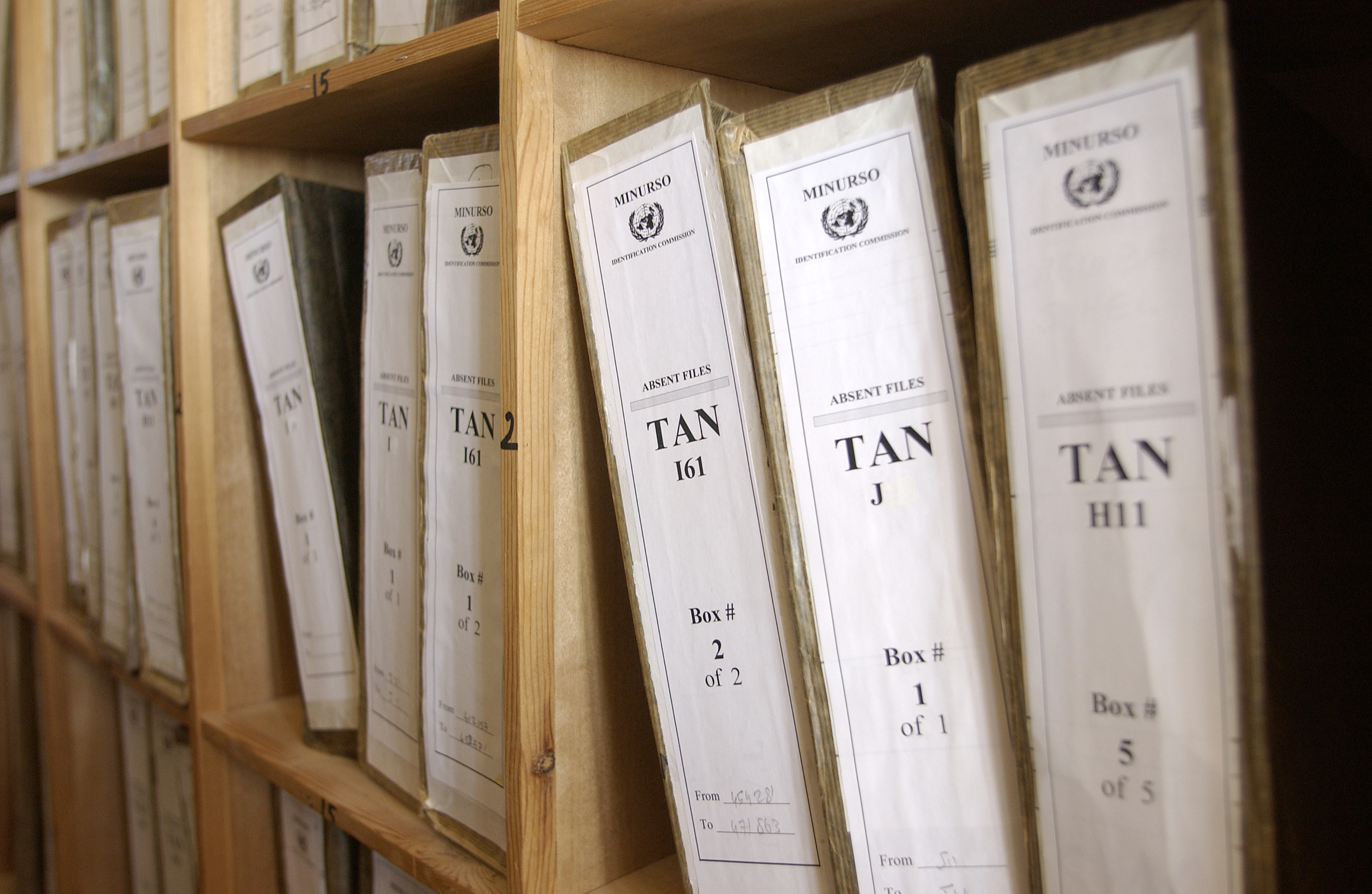

Photo: In the 1990s, the UN identified the voters to take part in the UN referendum, that Morocco later blocked. The registry is stored in Geneva - as well as in the refugee camps, where this picture is taken. @UNPhoto/Evan Schneider

The latest UN Security Council resolution on the peacekeeping mission in Western Sahara, resolution 2797, has drawn unusual attention this year - largely because of its reference to “Morocco’s Autonomy Proposal” as a possible basis for renewed talks. Some international media outlets have presented this as a diplomatic victory for Morocco, or even as a sign that the UN has shifted away from supporting the Saharawi people’s right to self-determination.

That narrative, however, does not withstand closer scrutiny.

What the Resolution says - and doesn’t say

Adopted in late October 2025, resolution 2797 does not abandon the UN’s long-standing objective of achieving a political solution that provides for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara.

The document has not yet been uploaded to the UN website, but can be downloaded here.

The text states that the Security Council:

“Calls upon the parties to engage in these discussions without preconditions, taking as basis Morocco’s Autonomy Proposal, with a view to achieving a final and mutually acceptable political solution that provides for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara...”

In other words, self-determination remains the guiding principle. The Council’s language is careful - perhaps deliberately so. It does not endorse Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara, nor does it exclude independence as a possible outcome. As legal scholars have pointed out, resolution 2797 cannot be read as overriding the peremptory norm (jus cogens) of self-determination.

Nevertheless, the UN now finds itself walking a difficult line. By explicitly referring to Morocco’s autonomy proposal without making equal reference to the Saharawi position, the Security Council risks creating a perception of implicit recognition of Moroccan control - something that would stand in tension with international law, the UN Charter and past UN practice.

“If the UN begins to accommodate de facto occupations in the name of “realism,” it would set a troubling precedent: are we ready to settle territorial conflicts outside the framework of international law?”, asks Sylvia Valentin, the Chairperson from Western Sahara Resource Watch.

At the same time, the explicit reference to Morocco’s autonomy plan could put pressure on Rabat to finally disclose what this plan actually entails. Despite being promoted since 2007, the autonomy proposal has never been presented in detailed legal or institutional terms. Morocco first began referring to an autonomy plan in the early 2000s. The points presented to the Security Council in 2007 had been in preparation for at least 4 years. In his briefing to the Security Council last year, the current UN Envoy for Western Sahara, Staffan de Mistura, urged Rabat to explain how the plan would allow for “some credible and dignified form of self-determination by the people of Western Sahara, and under which modalities.” To date, Morocco has offered no such clarification. On 10 November 2025, Morocco’s royal cabinet announced consultations to “refine the autonomy initiative proposed by Morocco within the framework of its sovereignty and territorial integrity”.

It is also worth recalling that the Frente POLISARIO submitted its own proposal to resolve the conflict in 2007 - one that kept all options open, from independence to integration into Morocco, to be decided through a genuine act of self-determination via referendum. For the first time, this position is absent from the Security Council’s language, even though the Saharawi president recently reiterated POLISARIO’s readiness to engage in unconditional negotiations in line with international law.

The text of the resolution was drafted and negotiated under US leadership. President Donald Trump, who in 2020 infamously announced his recognition of Morocco’s untenable claim to Western Sahara via tweet, has in recent months been promoting a push to “resolve” the conflict by the end of the year, as part of a broader effort linked to his Abraham Accords diplomacy and his quest for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Criticism from former UN Envoy

Former UN envoy for Western Sahara Christopher Ross has sharply criticised the resolution, describing it as “a step backward” that weakens the UN’s neutral stance. In a recent op-ed, Ross argues that resolution 2797 undermines the balance that previous UN texts tried to preserve between Morocco’s proposal and that of the Saharawi side.

According to Ross, the resolution’s new emphasis on the autonomy plan risks “favouring one party over the other” and jeopardises the credibility of the UN process. He warns that this shift could erode the Council’s ability to act as an impartial broker and might embolden Morocco to entrench its occupation further.

Ross, who served as the UN Secretary-General’s Personal Envoy for Western Sahara from 2009 to 2017, reminds that self-determination - not autonomy - remains the legal and moral foundation of the UN’s engagement with the territory.

Natural resources and economic exclusion

In the run-up to the UN Resolution, the UN Secretary-General’s most recent report on Western Sahara (S/2025/612) had shed light on a critical dimension often overlooked in coverage of the resolution: the ongoing exploitation of Western Sahara’s natural resources and the economic marginalisation of the Saharawi people.

In paragraph 73, the report notes persistent concerns about unequal access to employment and resources in the territory. Earlier paragraphs also recall the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) rulings, which found that EU trade and fisheries agreements with Morocco breach the right of the Saharawi people to self-determination by treating Western Sahara as part of Morocco without their consent. Paragraph 71 refers to UN special procedure mandate holders having sent a communication to Morocco citing “human rights abuses linked to coastal development projects that entail large-scale land acquisition, destruction of private property and displacement”.

These passages underscore that, even in the UN’s own assessment, economic activities in the territory remain intimately tied to its unresolved political status, and that the Saharawis’ exclusion from decisions over their land and resources continues.

A blow, but not the end

While resolution 2797 represents a diplomatic gain for Morocco, it is not the end of the story for Western Sahara. The UN framework still rests on the principle of self-determination, and no Security Council resolution can erase that legal foundation.

The challenge now lies in ensuring that the UN and its member states do not allow political expediency to erode international law. The Saharawi people’s right to decide their own future remains intact - even if it has been temporarily overshadowed by the language of “realism” and “compromise.”

Voting dynamics and context

UN resolution 2797, which renews for one year the mandate of the UN peacekeeping mission in Western Sahara (MINURSO), was approved with 11 votes in favour, 3 abstentions (China, Pakistan and Russia – all criticising the text’s imbalance or failure to uphold self-determination) and one member refusing to participate in the vote (Algeria).

Several members who voted in favour clarified their position afterwards. The representative of the Republic of Korea stated that the text should not be interpreted as prejudging the outcome of negotiations between the parties, Slovenia stressed that talks must “take place on equal footing and take into account the positions and proposals of all parties”, while Guyana emphasized that a settlement should be “one that provides for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara”.

MINURSO was established by Council resolution 690 (1991), following the 1988 UN-Organization of African Unity settlement proposals accepted by Morocco and the Frente POLISARIO. The proposals provided for a transitional period leading to a referendum in which the people of Western Sahara would choose between independence and integration with Morocco. That referendum – blocked by Morocco ever since – remains the unfulfilled promise at the heart of the UN peace process in Western Sahara.

Since you're here....

WSRW’s work is being read and used more than ever. We work totally independently and to a large extent voluntarily. Our work takes time, dedication and diligence. But we do it because we believe it matters – and we hope you do too. We look for more monthly donors to support our work. If you'd like to contribute to our work – 3€, 5€, 8€ monthly… what you can spare – the future of WSRW would be much more secure. You can set up a monthly donation to WSRW quickly here.

WSRW calls on addressing plunder

WSRW calls on UN Member States to address Morocco's plunder of Western Sahara during Morocco's UPR review in November.

WSRW calls upon UN to halt the plundering

In its statement to the United Nations’ Special Political and Decolonization Committee (Fourth Committee), Western Sahara Resource Watch called for the establishment of a mechanism to place the proceeds from the exploitation of Western Sahara’s natural resources under international administration until the conflict has been resolved, and for the inclusion of a human rights component into the MINURSO mandate.

States urge Spain to respect Saharawi rights in Human Rights Council

Namibia and East-Timor have today recommended Spain to respect the Saharawi people's right to free, prior and informed consent with regard to the exploitation of Western Sahara's natural resources.

WSRW calls on UN Members to question Spain on Western Sahara at UPR

Next month, Spain’s human rights track record will be reviewed by the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. WSRW asks UN Member States to raise the rights of the people of Western Sahara, for whom Spain continues to bear responsibility.